Megalopolis (2024, Coppola)

Time Stop

A little autobiography: My dad introduced me to Francis Ford Coppola through Apocalypse Now. First by way of his incessant quoting of the movie, particularly the immortal “I love the smell of napalm in the morning” line, and then via the DVD (theatrical, not redux) we had found in a $5 bin at a Walmart on a road trip. Then I watched Jack on HBO Family—I have no recollection of it other than the fact that I have seen it and that a lot of people think it’s bad. (I will reserve my own judgment until I have an opportunity to revisit it.) Following that, my grandfather sat me down in front of The Godfather Parts I & II–I remember being somewhat confused by TG I and enjoying TG II more at the time, but I’ve since revisited the first one more often and more warmly. I think I watched The Conversation on an iPod at some point; I just remember the final shot. I still haven’t seen The Godfather Part III all the way through, and I just saw The Rain People in anticipation of Megalopolis on a very comfortable couch with a friend who often opens me to new movies and new ways of seeing them—I had a great time with it. If you thought Vincent Gallo’s vision was sui generis, just get a load of that one.

All of which is to say: each FCC movie is singular and wedded to particular circumstances (both their creation and my viewings of them) and at the very least slightly inexplicable because of this personal nature. Megalopolis is, of course, no different. I'll do my best.

I had been looking forward to it for a very long time–rumors about its gestation circulated as early as the late 2000s, when I became a cinephile. (Perhaps even before, but I wouldn’t know.) It was going to be the 21st century answer to Metropolis, that much I knew and, 97 years later, it arrived. Battered and bruised by just about any production or distribution mishap one can imagine, it limped into multiplexes unceremoniously, and it will scurry away just as quickly. It will also certainly be reclaimed in 20 years. Then again, time is happening faster, so it might be closer to ten. I can see the think pieces in my mind's eye: “What Francis Ford Coppola got right about the 2020s.”

But what about now?

Memento Mori

As polemic? Inchoate and marble-mouthed, although not without its charms. It’s as if Coppola put every idea he’s ever had into this. Some are compelling, and those that aren’t are at the very least told with sound and fury: there are so many references to the classics that it’s kind of like Deadpool for Boomers. My favorite moment by far, for example, is when Adam Driver holds up a copy of Siddhartha for half a second, and the camera racks focus to it then racks away in the span of a blink. I wanted more silly intelligentsia drops such as that, like when (in the same scene) Driver claims that many are not worthy of plumbing his “deep, Emersonian mind.”

But really this is more about cinema than about society. If it is about How We Live Now, it’s simply saying that the American Empire has grown corpulent and rotten, but with a little verve and elbow grease it can be polished.

Coppola the cultural critic, while loud and bombastic here, does mercifully often sit second string to Coppola the filmmaker, who is shouting the last, sharp gasp of a dying visual language. Every movie decade is in here–at times it feels like every movie ever made is in here. It has the treacly sentimentality of the melodramas from his childhood. It has noir shadings. It has Koyaanisqatsi. It has The Night of the Hunter, The Invisible Man, and Revenge of the Sith. It has more Sith than any other movie, actually: Coppola picks up the Digital Opera baton where Lucas left it back in 2005, and the result is as strange and beguiling as that sounds.

As such, performances range in quality. Some actors know the kind of movie they’re in, some don’t. Driver is at his best when he’s imitating Claude Raines; Aubrey Plaza is always in Hyde mode, no Jekyll in sight–LaBeouf matches; Nathalie Emmanuel fails to pull off her screwball moment and never quite recovers; Esposito often seems confused, as does Voight, yet Voight interpolates that into his character; Hoffman is a non-entity. Fishburne fares the best, actually, as the pseudo-historian/Coppola stand-in.

Dum Spiro, Spero (or, In Vino Veritas)

The movie is wildly successful, however, in its most important respect: preaching the notion of an open dialogue and creating space for many contradictory ideas to coexist, and maybe to create positive action as a result of that coexistence. In short, cosmopolitanism.

No other movie in recent memory has captured the spirit of cosmopolitanism as well as Megalopolis does: the feeling that the movie we’re seeing takes place in a big city, with a lot of things going on, and all of them matter. So solipsistic have our movies become that they neglect that other stories are happening outside the boundary of the frame. Not so here. It’s the kind of bright-eyed cosmopolitanism that reminds me of

Kingdom Come:

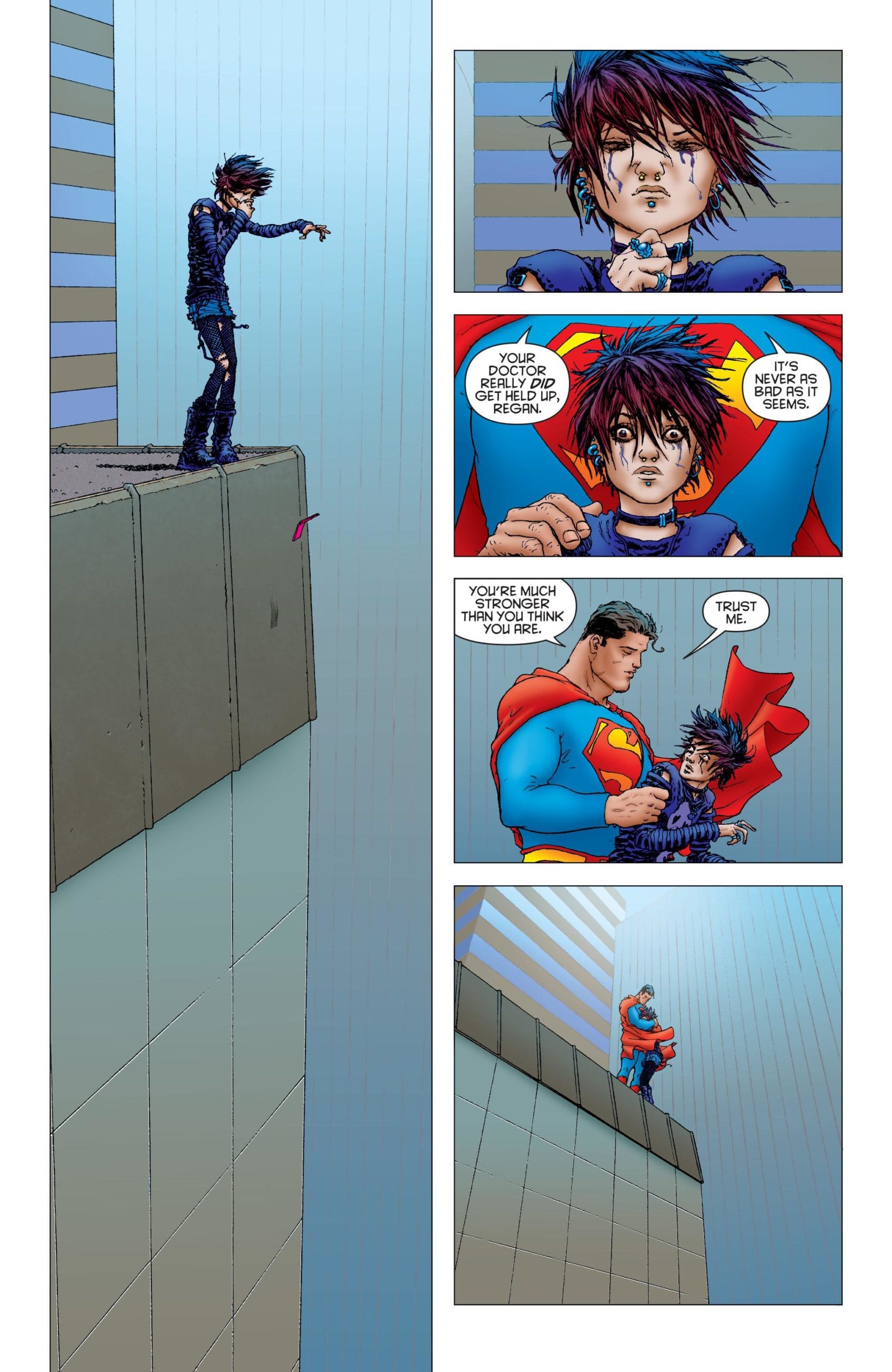

or All-Star Superman:

And come to think of it, more comic book movies should be like this. Zack Snyder tried, God bless him, but I think his sensibility is too dour. Give Coppola the keys to the DC castle! Isn’t that what comic books are for, anyway? To hold up a funhouse mirror to our own society? Isn’t that what Megalopolis strives for?

In that sense, Megalopolis is a statement of purpose.

During my Tuesday night (sold-out, although the theater was practically empty) showing, an unhoused woman had the seat next to me. I used to really dislike the word unhoused, mostly for the way it sounded coming off the tongue. Homeless felt warmer, the elitist's safe response to dehumanizing the poor. And yeah, I was tense when I sat down. A million negative scenarios scrambled into my skull; snooty muscle memory. Not as tense as the guy behind me, evidently, who walked all the way to our row to admonish her for talking through the trailers. "What, you don't love the magic of Hollywood?" she retorted. That put me at ease, and I rather enjoyed her commentary on some of the upcoming pictures. An explosion of enthusiasm for Conclave was my favorite: "Holy fuck, did Gore Vidal write that?"

She became quiet once the movie started, and I intended to ask her what she thought about it after it ended. Everyone deserves to enjoy movies, and considering this film’s ambition I felt her opinion to be of particular use; she would’ve offered it freely, I’m sure. She left about halfway through to go home, however, which probably says more than anything I could write. Home? Yes, home. Does she have permanent housing? Hard to say. But she does have a home: it's New York City. Ideas. They change us. They can open our hearts.

And now I’m about to teach Heart of Darkness to 11th graders. The idea that had been planted in me by Coppola almost twenty years ago, I now get to share with them. That’s where the profundity lies here. Not in what Coppola is saying, but in the act of saying anything at all. There’s great power in that. A superpower, you might say.